Recently, the term SDGs is popping up everywhere in phrases such as “initiatives for achieving SDGs,” “contributions to SDGs,” and so on. Even those of you who don’t know what SDGs are have surely seen these phrases, although you may not have taken special notice. The color-wheel badge that businessmen, politicians and so on are sporting on their jacket lapels is the main SDGs logo.

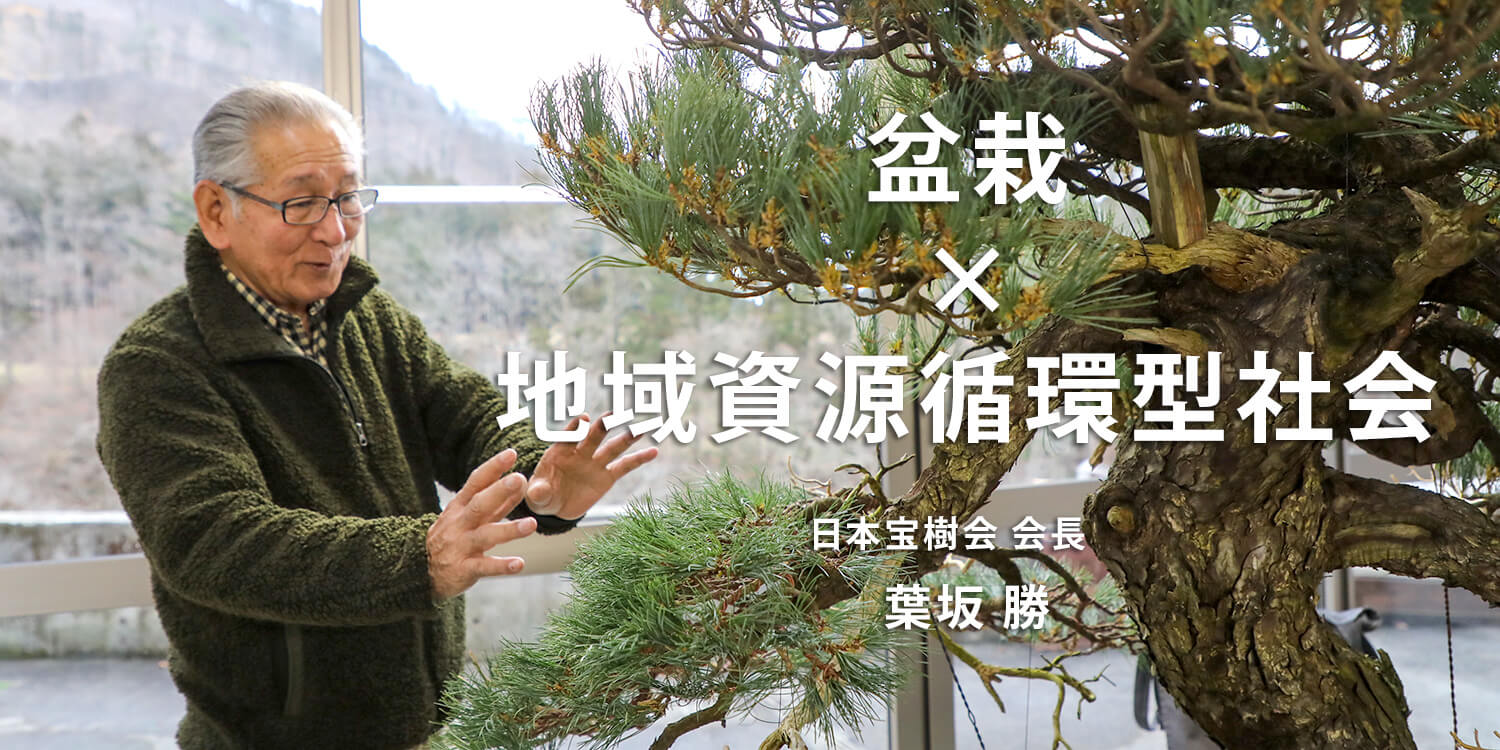

SDGs is the abbreviation for Sustainable Development Goals and is pronounced as S-D-Gs, and is often interpreted as “goals for passing on this beautiful earth to future generations.” These SDGs were adopted at the United Nations summit in 2005. However, there is an enterprise in Miyagi Prefecture which for more than 50 years has been carrying out research and development towards the goal of “realizing a society that recycles regional resources.” Their environmental symbiosis plant, called a Hazaka Plant, uses the power of bacteria to rapidly ferment and break down organic waste matter. The company has been awarded various patents both domestically and globally, and its symbiosis plants are held in high regard in business and political circles. Over the years, president and plant developer Masaru Hazaka has unquestionably experienced countless days filled with effort and hardship. However, he never speaks of the plant as his own invention nor puts on airs, humbly stating “it is all thanks to the people of long ago, it’s what Japanese have been cultivating since ancient times. There’s nothing important or amazing about me”. We paid a visit to Mr. Hazaka, who represents bonsai fanciers of Japan and serves as the president of the Nihon Houjukai.

1/2: Japan’s achievement during the Edo Period

Returning waste matter to soil in the right way

In the latter half of the 19th century, terrible odors emanated from the Thames River flowing east to west in London. At that time, flush toilets had started to become popular, with the waste water being pumped directly into the Thames. Households without flush toilets threw the waste accumulated in bedpans down water channels or into the river, while unmannered people living on upper floors threw it down to the street from their windows. The situation was the same in neighboring Paris. In Japan, this time equates with the Edo Period (1603-1868). What were things like in towns then? Mr. Hazaka is emphatic in his reply.

“Since ancient times, Japanese have bowed their heads before eating, saying ‘I gratefully receive this meal,’ and ‘Thank you for this food’ after completing each meal. They verbally express gratitude when receiving the life of animals and plants—nature’s bounty. There’s no equivalent phrase for ‘I gratefully receive this meal’ in English, is there? I mean, no set phrase that expresses our gratitude toward nature. In Japan we came to use a cyclic system where we properly return waste matter to soil, which is then used to produce more life, and the whole process starts again. “This concept of properly returning waste matter to soil is nature’s providence and is the most important basis for a resource recycling society. But nothing in the teachings of any school or religion, be it Buddhism, Islam, Christianity, or other, tells us how to manage waste. And in recent years, as culture and the economy have developed, our lifestyles have become richer and more convenient; we have started throwing things away and stopped recycling resources.

“In Japan, waste matter was initially used for fertilizer commercially during the Kamakura Period (1185-1333). By the 1600s, the shogunate issued government ordinances on the separating, collection, transport and disposal of rubbish, and in particular, excreta (night soil) was called ‘chemical fertilizer’ and put into circulation to enrich regional agricultural land and increase agricultural productivity. Although this concept of recycling in Japan was non-existent elsewhere, it was hygienic and resulted in a society that recycled its regional resources. During this same period, Europe was under siege from the plague, cholera and other contagious diseases, yet there was little spread of such illnesses in Japan. One could say this is how Tokyo went on to become a major city with a population of more than one million.”

Not burning, but returning completely composted waste to the soil

Using the knowledge of these forebears and lessons learned from nature as a base, Mr. Hazaka developed Japan’s first high speed composting process facility, Hazaka Plant, in 1976. In the natural world, it takes years to recycle organic waste back as a resource, but with the help of bacteria, the Hazaka Plant can completely transform waste into compost in only 25 days.

“Did eczema or hayfever exist in the olden days?” Mr. Hazaka asks. “No, they didn’t. So why do we have them now? It is because we burned and killed all the bacteria that protect humans. Did you know how many waste incineration facilities there are in Japan? According to Waste Management in Japan, a white paper prepared by the Ministry of the Environment (published 2017), the government alone manages 1103 incineration facilities. Compared with other foreign countries, this is an extraordinarily high number. Rather than burning everything, we need to work seriously to create a system that recycles resources–just like we did back in the 1600s.”

<Continue to 2/2>

Profile

Hazaka Masaru

Born in Miyagi Prefecture. Developed Hazaka Plant in 1976 and established Kennan Eisei Kogyo as an independent business. In 1981, Kennan Eisei Kogyo Co., Ltd. was incorporated with Hazaka as its CEO. He began working with bonsai around 50 years ago and is also president of the Nihon HoujuKai.